In the early to mid-Victorian era, cities and towns in England were in a bad way. They were horribly overcrowded and sickness was rife thanks to the hideously inadequate sanitary facilities. Little or no sewerage, polluted drinking water, and general filth in the streets led to typhoid and cholera epidemics and death on an almost unprecedented level (the Black Death excepted). The problems were exacerbated by hotch-potch local authorities who had no money to invest in things like water supplies and street cleaning.

By the late 1850s, it was reaching crisis point. Well, what is was really, was that the rich started to realise that death from cholera wasn't something that just affected poor people. The levels of filth, far from just being unpleasant, were downright dangerous for people of all classes, funnily enough. In 1858 came the Great Stink. It was summer, always a time when things in overcrowded London became a bit stinky thanks to the vastly overcrowded streets and very poor facilities. Historically, London's citizens would get their water supply from the Thames, with specially-built waterwheels helping pump water to households. The first waterwheels were built in the 1580s, with a further one added in 1701 and, says Wikipedia, these remained in place, pumping away, until 1822. Unfortunately, in 1815, human waste started to be pumped out from the sewers into the Thames. How anyone thought it was a good idea to pump poo into the city's main water supply to be resupplied to households, I really don't know. But they did. Then, there were the cesspools. Two hundred thousand of these, with gallons of waste being emptied from newfangled flushing toilets. They often overflowed into the streets. The smell must have been pretty bad most of the time.

A few things in the years previous to the Great Stink helped the powers that be realise that something had to be done. First, it was the discovery of the bacteria that caused cholera - previous to that, scientists (and plebs) believed that disease was caused by miasmas - clouds of stink. And in 1854, John Snow linked cholera to water supplies after he he discovered a community in Soho were all being poisoned by the well in their square. He put two and two together when he discovered the only people not getting ill were a group of Irish navvies who only drank beer, never water. He broke the handle off the pump, which is still there too this day! The government then slowly started to overhaul the sewer systems. But then, in 1858, it was exceptionally hot. The cesspools, combined with the stench from the Thames itself, overwhelmed London.

No one could take it. Cholera and the Thames says, "Even the elite were not exempt from such an odious odour: ‘The intense heat had driven our legislators from those portions of their buildings which overlook the river. A few members, indeed, bent upon investigating the matter to its very depth, ventured into the library, but they were instantaneously driven to retreat, each man with a handkerchief to his nose.’

The managers of the House of Commons tried preventative measures like soaking curtains in chloride of lime to try and 'filter' the smell, and lots of companies considered evacuating to the home counties. Rain finally put a stop to the nasal assault and ended everyone's stinky misery but luckily, this whole experience finally pushed the government to act.

Joseph Bazalgette, superstar civil engineer of the age, was hired to transform the sewer systems. He built embankments on the Thames, designed 82 miles of new brick-clad underground waterways and 1,100 miles of street sewers. Brand new pumping stations were built on the edges of town where the waste was still pumped into the Thames, albeit outside of London. Oh, Victorians. (They later built treatment works, thank goodness).

One of these pumping stations, built in 1865, was Crossness. Here it is today - on the one hand, not *that* exciting to look at, on the other, it's a darn sight nicer than anything we build today. It was lower than the original drawings (above) and extended on the left-side much later. It is no longer in use, but it's been partially restored as part of an ongoing project. So inside, parts of it are exactly as it would have been in April 1865, the day Albert Edward, Price of Wales, opened it.

Let's have a look around Balzagette and the Metropolitan Board of Works' masterpiece of engineering. Packed with cutting edge technology for the time, it is also absolutely stunning.

Hard hats are a requirement in Crossness. Something I didn't consider when I

did my topknot that morning!

did my topknot that morning!

Crossness was closed and abandoned in the 1950s as technology moved on and it became obsolete. Vandals and thieves took over, stealing the brass handrails and bits and it became derelict. It took until 1987 to be recognised as the marvel of Victorian craftsmanship it is. The volunteers restoring it found scraps of the original paint and have returned much of the interior to its former glory.

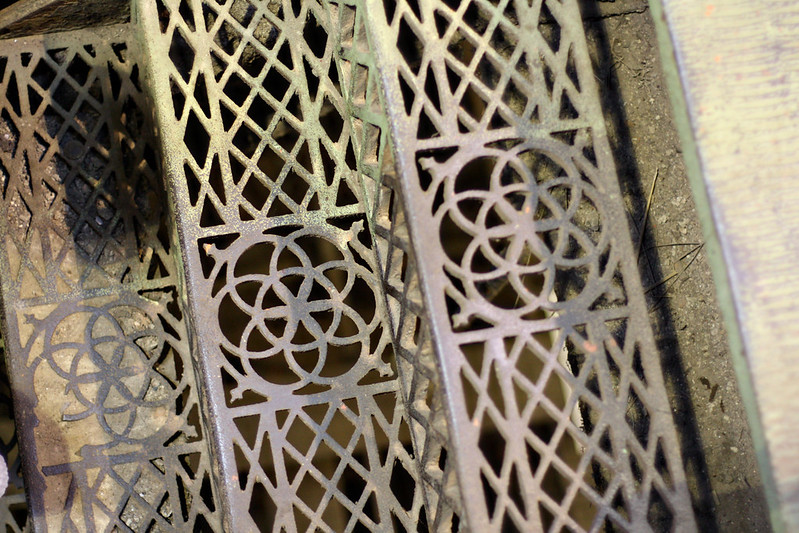

Remembering all the while that this is a facility used exclusively for pumping human excrement, it is astonishingly beautiful. The floors, walls and ceilings are all exquisite, even the bits that haven't been restored yet.

And the bits that have been replaced have been done so carefully, to keep to original specifications.

This is the original entrance, before it was extended in 1897 to add four more pumps.

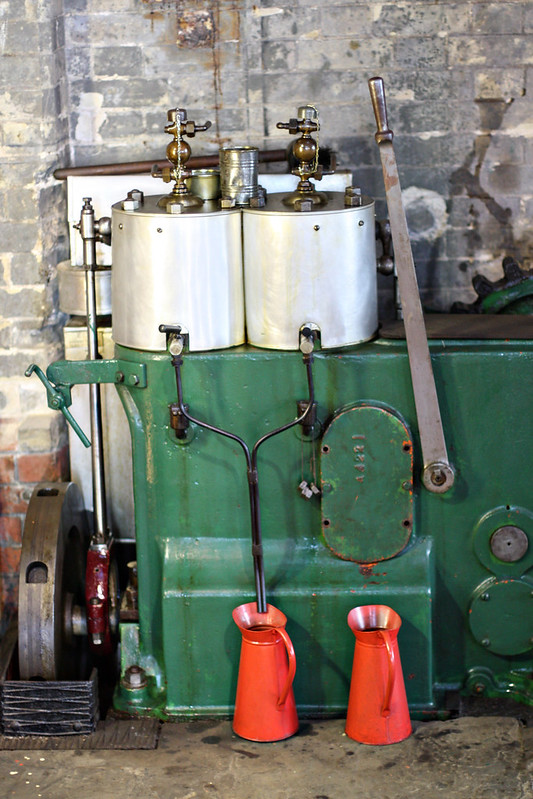

Crossness has four massive pumps, 'Victoria', 'Prince Consort', 'Albert Edward' and 'Alexandra'. Prince Consort has been completely restored. Victoria is in the works. Sadly, Albert Edward is still looking pretty grotty, but it's impressive nonetheless.

Check out Prince Consort in action. It's turned on for special visitor days at Crossness, pumping nothing at all, of course. But it's a beauty to behold. So huge (40 tonnes!) and the motion is so smooth!

The reason our hero opened the sewer system in 1865 was because, at that time, it was a mere four years after the death of Albert, the Prince Consort. Queen Victoria was in a state of deep mourning, the same state she remained in for the rest of her life. Thus, the official tasks fell to Albert Edward.

I like to think his Future Majesty enjoyed officiating at these openings. At least I hope so, since he had to do so many of them!

The Crossness Engine Trust is only open every once in a while but it is so worth a visit. You get a very small idea of what the Great Stink must have been like as you walk through the newer sewage works to get to the main event. The café is unbelievably cute, serving egg rolls and cakes made with no frills by the volunteers. And Prince Charles, the current Prince of Wales has even been there, bringing history full circle.

My fab dress is by Time Machine Vintage on Etsy

Thanks as ever for reading and those Brits reading who have always wanted to try some King's Ginger for yourselves, good news. It's now available in all Waitrose stores! Hurrah!

Do fan KGL on Facebook to find out about some upcoming tasting events too. That's all for now... wishing you a very unstinky bank holiday weekend,

Fleur xx

DiaryofaVintageGirl.com

0 comments:

Post a Comment